This

paper was written with the intention of submitting it to Hopewell Culture

National Historical Park, for their online newsletter, Hopewell Archaeology. The paper is written for general readers. It

was compiled in Carbondale, IL in 2011, using ESRI ArcMap GIS software.

Landscape as Lens: Understanding Hopewell

Eclipse Prediction Capabilities at the Newark

Earthworks

Christopher S. Turner

2011

The Hopewell geometric enclosures have long

fascinated anthropologists and lay folk alike. Since the early 1980s,

researchers have suggested that these large earthworks may have functioned as

sighting devices designed to monitor sunrises and moonrises. With regard to

sunrises, it can be demonstrated that any resultant calendrical knowledge would

have contributed to the accurate timing of the planting and harvesting of food

crops, what anthropologists call “subsistence scheduling." Less apparent

is the role that the monitoring of moonrises may have played.

Ray Hively and Robert Horn of Earlham College in

Richmond, Indiana have written several papers concerning the use of the

Hopewell earthworks and their ability to delineate various moonrises along the

horizon (Hively and Horn 1982, 1984). Especially interesting is their research

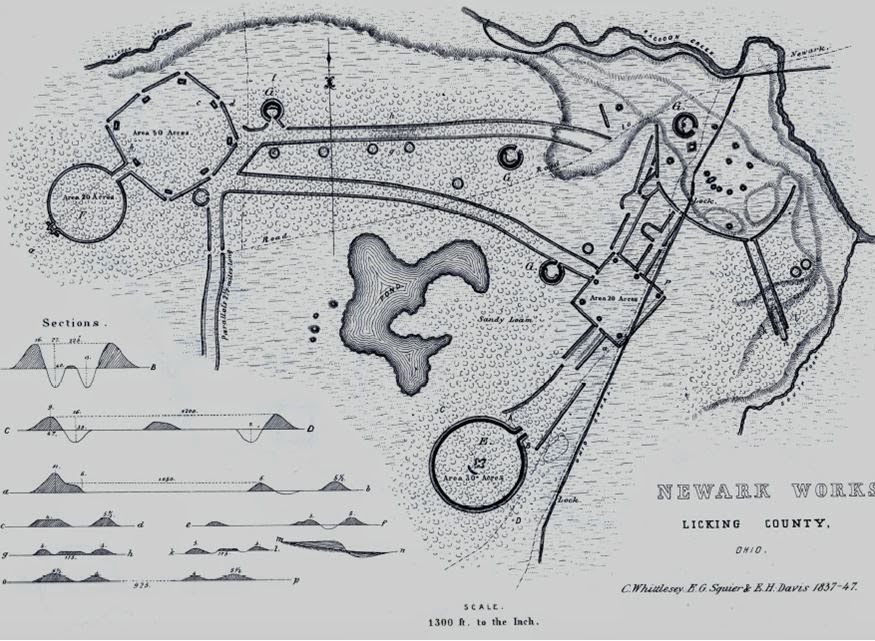

regarding the octagonal shaped enclosure in Newark, Ohio (Figure 1). They

discovered that the octagon marks the various rise and set points of the moon

as manifested during its 18.6 year cycle. Because the lunar orbit is tilted

five degrees relative to the earth’s orbit around the sun, its extreme

positions along the horizon differ from those of the annual movement of the sun

between summer and winter solstice. Additionally, the lunar orbit wobbles or

precesses in a period of 18.6 years. What this means in effect is that the

moon’s extreme rise and set points along the horizon differ from those of the

sun. The moon reaches these extreme locations only for relatively brief

intervals twice every 18.6 years. Hively and Horn demonstrated that the Newark

Octagon earthwork indexes these extreme lunar rise and set points, which are called

the lunar extrema or lunar standstills.

In 2006, the researchers from Earlham College

published a statistical analysis of their earlier work. They found that the

assortment of calendrical sightlines at the Newark Octagon would not occur

randomly except in very rare cases. This statistical evidence creates a strong

argument that the lunar angles evidenced at the octagon were intentionally

encoded by the Hopewell who built the enclosure some seventeen or eighteen

centuries ago.

The members of Hopewell society who designed this

and the other geometrical mounds that were used to monitor the heavens were likely

to have been elite individuals among their people. Anthropologists refer to those

who possessed such esoteric knowledge as calendrical

specialists. These elite members of Hopewellian society would have been

accorded special status, and they likely had the ability to organize the large

parties of workers that would have been needed to construct the massive

earthworks. The question arises, just how did they gain their elite status?

The current archaeological record suggests that the

Hopewell were involved in raising various plant foods that contributed in part

to their overall diet. Paleobotanists refer to these various seeds and the

plants that they came from as the Eastern Agricultural Complex (Smith 1995, Wymer

1997). As evidenced in the archaeological record, the use of these cultivated

foods increased in the same era as when the large enclosures appeared (Case and

Carr 2008:86-88). We can assume that the elites who maintained the Hopewell

calendar monitored the various sunrises in order to maximize the output of their

cultivated plant foods. This much is straightforward. Less obvious is why the

same specialists would be concerned with the motions of the moon, and in what

manner it would add to their social status by doing so (Reyman 1987:130).

The answer may lie in the arrangement of the

earthworks themselves, and in their placement on the local landscape. Studies of

the landscape with regard to the siting of monuments fall under the category of

phenomenology. Also called landscape archaeology, this investigative tool has

been developed in Britain where there is a great array of earthen and stone

monuments to be found. The lens of phenomenology is also well suited to

examining the network of Hopewell geometric earthworks found in Ohio. An

assessment of the earthworks in Newark focusing

on their placement across the local landscape can be offered.

First, we must examine the location of the

earthworks themselves. In Newark, there are two extant large sites to consider:

the Octagon Earthworks and the Fairground Circle (Figure 1). The latter is a

large circular earthen enclosure with a single opening or gateway. When viewed

through this singular opening from the center of the circle, the sun will rise

along this sightline in early May (Turner 1982, 2004). This interval in the

calendar is an ideal planting time in Ohio. There is even an old folk saying

reflecting this, which says that the corn farmer will lose “A bushel a day

after the eighth of May” by planting after that date. (Mike Van Dorn, personal

communication 1983). To plant sooner means to risk losses due to a late freeze.

Evidence of use of the early May planting index in ethnographic records of

other Native American societies can be found. The Hopi Indians of Walpi Pueblo in

Arizona were known to have marked this planting interval, calling it neverktcomo (Forde 1931:384-386). They

called the month preceding this date “the waiting month” (hakiton muya), referring to the need to wait till the chance of a

late freeze had passed (Malotki 1983:357, 374-377). Historically this

calendrical division in early May is called a “cross quarter date”. This form

of calendar simply divides the year into eight equal parts, instead of the four

seasons that we use today. It was commonly used in Europe during the Middle Ages

for instance. Our Groundhog Day and Halloween are remnant holidays from the old

cross quarter calendar (McCluskey 1989).

The idea that the Fairground Circle was utilized for

establishing the planting calendar is consistent with the idea that elite Hopewell

specialists were regulating subsistence scheduling. But again, what advantage

would be gained by these specialists in monitoring the location of the moon’s

various rise and set points, the lunar extrema or standstills?

It is here that phenomenology can be useful. First,

it is necessary to describe the manner in which these various calendrical

sightlines function. There are three points on the landscape that must be

defined.

First , the individual making the observations must

stand in a particular location. In studying archaeoastronomy, we call this

location the “backsight”. The backsight at the Fairground Circle is located at

the Eagle Mound at the center of the great circle. At the octagon, the primary

backsight is located on the southwest end of the earthwork at the so-called

Observatory Mound.

Secondly, the part of the earthwork toward which the

observer sights is called the “foresight”. At the Hopewell geometric

earthworks, the foresights are defined by the gaps or gateways between the

earthen embankments. At the Fairground site, the singular gateway or opening in

the circle is the foresight (Figure 2). At the octagon, the primary sightline

is defined by the gaps along the main axis of the overall earthwork. As pointed

out by Hively and Horn, various combinations of other gateways located at the

vertices of the octagon embankments form the backsights and foresights for the

remainder of the lunar extrema sightlines that they found.

Thirdly, each of the various calendrical sightlines

defined by the earthworks terminate somewhere along the surrounding horizon.

These locations are called aptly enough the “horizon foresights”. It is these

horizon foresight loci that are essential in understanding the overall design

and placement of the earthworks on the landscape, and that give insight into

their use and function.

The creation and observational use of horizon

foresights can be found in many examples across cultures around the world. The

Inca of Cuzco in Peru marked solar rise points using stone pillars as horizon

foresights (Dearborn, Seddon, and Bauer 1998). The Hopi in Arizona indexed the

various days of the year by marking where the sun would rise along the horizon.

They memorized these locations and performed rituals at some of them (Stephen

1936:60, 82, map 4; Zeilik 1985:S12). In many cases, horizon foresights will

occur at locations that form distinct topographical features, such as mountain

peaks or gaps.

With regard to the Hopewell, it is relatively easy

using modern GIS software or even topographic maps to determine the locations

of the horizon foresights that are delineated by the geometric earthworks. In

the case of the Fairground Circle, the sightline terminates on a bluff feature

that lies three kilometers from the circle itself (Figure 3). It is worth

noting that the horizon foresights suggested by the calendrical sightlines are

potential locations for archaeological research. These sites can be tested for

evidence of use as foresight locations. Archaeologists might expect to find

evidence of burned rock indicating that fires were set to aid in visual

sighting during calendrical observatrions. Or, there may be small earthworks at

some of these areas. Conversely, excavation may yield evidence of ritual

offerings at the various horizon foresight loci.

The situation is similar at the Newark Octagon.

Though Hively and Horn discuss the entire suite of eight lunar extrema or

standstills, I will only mention the primary sightline along the main axis of

the earthwork (Figure 4). This sightline terminates on a prominent hill that

lies some 5.7 kilometers from the Observatory Mound (Figure 5). This location is

also a prime candidate for archaeological exploration. If the lunar sightlines

are valid, as the statistics suggest, then there will almost certainly be archaeological

evidence of use of this horizon foresight by the Hopewell.

In examining the topographic maps, it became

apparent to me that the horizon foresight

for the Fairground Circle lay almost directly due east of the Observatory

Mound at the Newark Octagon. In astronomical terms this means that the equinox

sunrise might occur along a sightline

from the Observatory Mound to the Fairground Circle horizon foresight. To

answer this question, I checked the astronomical and topographic data, which

confirmed my suspicion.

Again, as seen from the Observatory Mound, the sun

will rise at equinox over the location that also serves as the horizon

foresight for the Fairground Circle sightline (Figure 6). What does this means

regarding astronomy or archaeoastronomy? In can be shown that during the 18.6

year lunar cycle eclipses can occur only at the full moon nearest equinox at the time of the lunar extrema or standstills. Thus,

if a person at the Observatory Mound noted equinox sunrise over the horizon

foresight to their east, and on the same day confirmed the moon rising at the

lunar extrema, they would have the ability to predict an eclipse from this

single backsight location. The geometry of this is inescapable.

In must be noted that this would likely apply to

only lunar eclipses. Solar eclipses would occur at the new moon during these

periods, but solar eclipses cover a small area of the earth’s surface, seen by

comparatively few witnesses . The opposite is true of lunar eclipses. A total

eclipse of the moon can be seen over more than 50% of the earth’s surface. Of

course, not all lunar eclipses are total. Some are so minor that they are not

visible even if you are looking directly at the moon and are expecting the

eclipse (these are the penumbral lunar eclipses).

In this regard, overall about 45% of the time, the

Hopewell could actually see an eclipse predicted by a calendrical specialist.

Nonetheless, this would be a significant number of successes, and the ability

to predict these would likely greatly impress the Hopewell people who were made

aware of the prediction. Inasmuch as elite status formation is suggested by the

ability to produce an accurate planting calendar, the same might be suggested by

the ability to predict the more evanescent eclipse of the moon.

If we consider the design of the Newark Octagon, it

is apparent that no part of the octagonal earthwork is utilized as a foresight

to mark the equinox. The equinox sightline is only indexed by the horizon

foresight in question, the one shared with and defined by the Fairground

Circle. It can be reasoned that the lack of any overt architecture marking the

equinox sunrise line may have been intentional. This may be indicative of the

effort to conceal the means by which the eclipse predictions were made. The

esoteric or hidden role of calendrical knowledge can be evidenced by examples

from other cultures across the ethnographic record (e.g. Reyman 1987:131).

Various researchers have recently suggested that the

Newark earthwork complex may have functioned as a ritual pilgrimage center

(Lepper 2006). These pilgrimage events are envisioned to have occurred at

appointed times in the Hopewell calendar. It is possible that some of these

gatherings may have been timed with regard to the 18.6 year lunar cycle.

Eclipse prediction may have been part of the drawing effect that lured pilgrims

to the site.

Whatever

the case, a considerable amount of organized labor was employed to create the

earthwork assemblage that was noted by early Euro-Americans in Newark. The

Octagon earthwork appears to have been the most complex and refined of all such

Hopewell enclosures. It is insufficient to suggest that it was constructed with

no other intent than to mark various moonrises that were otherwise without

cultural significance. The demonstrable ability of these earthworks to be

utilized as eclipse prediction devices may answer the “why” regarding their

construction.

References

Cited

Case, Troy D. and

Christopher Carr

2008 The

Scioto Hopewell and Their Neighbors: Bioarchaeological Documentation and

Cultural Understanding. Springer,

New York.

Dearborn, David S. P.,

Matthew T. Seddon, and Brian S. Bauer

1998 The Sanctuary of Titicaca: Where the Sun

Returns to Earth. Latin American

Antiquity 9(3):240-258.

Forde, C. Darryl

1931 Hopi Agriculture and Land Ownership. Journal of the Royal Anthropological

Institute 61:357-405.

Hively, Ray and Robert

Horn

1982 Geometry and Astronomy in Prehistoric Ohio. Archaeoastronomy supplement to the Journal for the History of Astronomy 13(4):S1-S20.

1984 Hopewellian Geometry and Astronomy at High

Bank. Archaeoastronomy supplement to

the Journal for the History of Astronomy 15(7):S85-S100.

2002 A Statistical Study of Lunar Alignments at

the Newark Earthworks. Midcontinental

Journal of Archaeology 31(2):281-322.

Lepper, Bradley T.

2006 The Great Hopewell Road and the Role of

Pilgrimage in the Hopewell Interaction Sphere. In Recreating Hopewell, edited by Douglas K. Charles and Jane E.

Buikstra, pages 122-133. University press of Florida, Gainesville.

McCluskey, Stephen C.

1989 The

Mid-Quarter Days and the Historical Survival of British Folk Astronomy. Archaeoastronomy supplement to the Journal for the History of Astronomy 20(13):S1-S19.

Malotki, Ekkehart

1983 Hopi Time: A Linguistic Analysis of Temporal

Concepts in the Hopi Language. Mouton Publishers, Berlin.

Reyman, Jonathan E.

1987 Priests, Power, and Politics: Some

Implications of Socio-ceremonial Control: In Astronomy and Ceremony in the Prehistoric Southwest, edited by John

B. Carlson. Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, Albuquerque.

Smith, Bruce D.

1995 The Emergence of Agriculture. Scientific

American Library, New York.

Stephen, Alexander M.

1936 Hopi Journal. Columbia University Press,

NY.

Turner, Christopher S.

1982 Hopewell

Archaeoastronomy. Archaeoastronomy

5(3):9. Center for Archaeoastronomy, College Park, Maryland.

2004 Middle Woodland Archaeoastronomy in Ohio.

Paper presented at the 7th Oxford International Conference on Archaeoastronomy,

Flagstaff, AZ.

Van Dorn, Michael

1982 Personal communication regarding local

folklore. Van Dorn is a long time resident of Newark, Ohio, and has provided

the author with detailed information concerning the Hopewell earthworks.

Wymer, Dee Anne

1997 Paleoethnobotany in the Licking River

Valley, Ohio: Implications for Understanding the Hopewell. In Ohio Hopewell Community Organization,

edited by William S. Dancey and Paul J. Pacheco, pp. 153-171. Kent State

University Press, Kent, Ohio.

Zeilik, Michael

1985 The Ethnoastronomy of the Historic Pueblos,

I. Calendrical Sun Watching. Archaeoastronomy

supplement to the Journal for the Histor

of Astronomy, 16(8):1-24.

Figures

Figure

1. Fairground Circle lower center, Octagon group upper left (Squier and Davis

1848)

Figure 2. Fairground

Circle lower left, with color-coded viewshed sightline, green = visible, red =

invisible. Sightline terminates on bluff feature three kilometers distant,

right.

Figure 3. Detail of

Fairground Circle sightline horizon foresight bluff feature.

Figure 4. The Newark

Octagon, primary axial sightline, color-coded for visibility

Figure 5. Detail of

Newark Octagon axial sightline foresight feature.

Figure 6. Equinox

sunrise as seen from the Observatory Mound at the Octagon group occurs over the

same horizon foresight as seen from the Fairground Circle’s cross quarter

sightline

The author grants permission to

reproduce text, tables, maps, or images included herein, provided that the

author is cited as Turner, Christopher S.,

year of article, name of article, conference event and date if applicable

to paper, page, and source, and provided that use of any text, tables, maps, or

images included herein is for non-commercial, academic purposes.

No comments:

Post a Comment